Babangida Reveals Unfulfilled Promise That Sparked the 1966 Massacre of Igbos

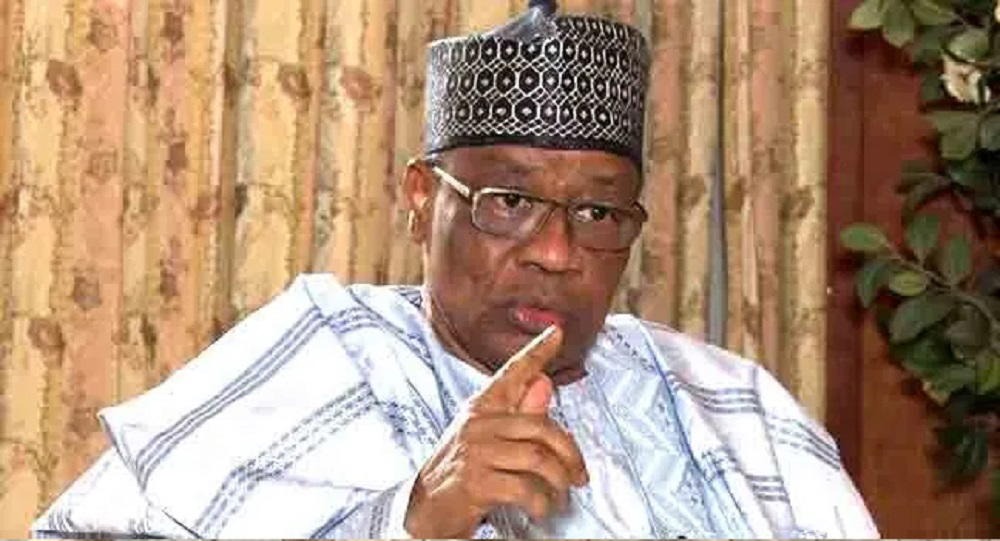

General Ibrahim Babangida, the former military head of state, has shared a startling revelation in his new book “Journey in Service”. He recounts how General Yakubu Gowon’s promise to ensure the safety of Igbos in northern Nigeria was tragically left unfulfilled, leading to the brutal 1966 pogrom in which thousands of Igbos were massacred across the north.

General Ibrahim Babangida, the former military head of state, has shared a startling revelation in his new book “Journey in Service”. He recounts how General Yakubu Gowon’s promise to ensure the safety of Igbos in northern Nigeria was tragically left unfulfilled, leading to the brutal 1966 pogrom in which thousands of Igbos were massacred across the north.

In his book, launched in Abuja on Thursday, Babangida reflects on the growing tension between Gowon and then Lt-Col. Emeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu, which marked the beginning of Nigeria’s descent into chaos. Babangida explains that Ojukwu, in a radio broadcast from Enugu, rejected Gowon’s leadership, arguing that, with the absence of Aguiyi-Ironsi, the most senior officer, Brigadier Babafemi Ogundipe, should be the rightful leader of the country.

This rejection from Ojukwu heightened the already volatile situation in Nigeria, with Gowon scrambling to restore national stability. According to Babangida, Gowon’s strategic move to release Chief Obafemi Awolowo, a prominent Yoruba leader, from prison was a political maneuver aimed at securing the support of the Yoruba people, who had been critical of the military government. But while Gowon succeeded in gaining the Yoruba’s favor, his commitment to the Igbos—assuring their safety in the north—remained tragically unfulfilled.

The massacre of Igbos across northern Nigeria began on September 29, 1966, just as Gowon’s peace talks were underway. The killings were both horrifying and widespread, driving thousands of refugees from the north into the southeast, sparking even more tension. In response, Ojukwu barred eastern Nigerian delegates from participating in further peace talks, claiming the lives of Igbos outside the east were at grave risk.

As the country teetered on the brink of war, Lt-General Joseph Ankrah of Ghana intervened, proposing a neutral location for peace talks. This led to the historic Aburi Conference in January 1967, which saw Ojukwu and Gowon meet to discuss the future of Nigeria. However, the outcome of the conference remains a subject of contention. While the eastern Nigerian delegation believed they had secured a loose federation agreement, the federal government interpreted the accords within the framework of a united Nigeria.

The differences in understanding came to a head when the federal government, in an attempt to implement the Aburi Accord, issued Decree 8, which Ojukwu vehemently rejected. Ojukwu’s boycott of a critical meeting in March 1967, where the decree was to be ratified, was the final straw. This disagreement over the interpretation of the Aburi Accord eventually triggered the Nigerian Civil War.

Babangida’s account of these turbulent events highlights the complexities and missed opportunities in Nigeria’s history—moments where peace could have prevailed, but instead, a tragic war began that would change the nation forever.